The weather was surprisingly mild for that time of year in Philadelphia, PA, and the conversations were lively as participants walked from the venues back to their hotel. One overwhelming refrain emerged from first-timers as they chatted with other IPAY-attendees: “I thought there’d be more text.”

Text-based work certainly isn’t disappearing in the international theatre community, but there is an ever-growing wave of artists creating theatrical experiences that are not anchored by dialogue or prose. TYA Today spoke with artists from around the globe about their experiences with non-verbal work in the field of Theatre for Young Audiences. They are generating work that exists in the realms of unspoken poetry and metaphor; movement and gesture; music and spectacle, and light. Many of these non-verbal experiences defy categorization and are hybrids of circus, classic clown, puppetry, mask work, video projection, live animation, and music. The work ranges from intimate to colossal; gentle to turbulent; high-tech to almost bare stage.

Text? Story? Narrative? Script? What are We Talking About?

At the most basic level, “text” is a written and spoken code used to convey meaning. If the audience is familiar with that code, they can decipher what the artist is trying to communicate. In western theatre tradition, the word “text” is often substituted by “script” or “dialogue” or “plot” and has been the primary vehicle for theatre-makers to transmit ideas. Aristotelian-based conceptions of drama further privilege text as the principal element that constitutes theatre and distinguishes it from other art forms. While design elements do play a role in the audience’s meaning-making process, in text-based work, they are not the most essential element. Non-verbal work not only departs from text as the central component, it also often diverges from linear storytelling structures with a clear beginning, middle, and end.

Defining non-verbal work is challenging. The very moniker “non-verbal” defines it by what it is not. What it is, and what it is possible to be, is vast and diverse. While artists often define “text” very differently, some have a complete aversion to using the term to refer to the audience’s meaning-making “map” of their work. “We want to circumvent the audience’s intellectual defenses and maximize their engagement,” Australian artists Arielle Gray and Tim Watts of The Last Great Hunt explain. They challenge themselves as theatre-makers by deliberately taking away words to tell a story. “It gets us out of our own heads and helps maintain a sense of play. It also allows the audience to take a more active role in being meaning-makers as they watch each element unfold. Meaning isn’t being narrowed into one specific interpretation.”

Serbian-Swiss choreographer and installation artist Dalija Acin Thelander seeks to “problematize socially limited sensory hierarchy that privileges that which we can perceive with our eyes and ears.” She asserts that this sensory hierarchy is aligned with social ranking, and favors the dominant group. This “ranking” often suppresses the senses of touch, taste, and smell because they are associated with the subordinate group (i.e., women, workers, and non-Westerners). Her work for babies and their caregivers offers a non-linear sensory experience that provides simultaneous stimuli from all sensory categories and gives babies more agency to explore the world she’s created for them. “When I use text,” Thelander states, “I do not approach it from the context of meaning/understanding of storytelling. I use it as just one element which is part of the larger ecology of performance, leaving a lot of freedom for interpretation and ways of experiencing it.”

Thelander, Watts, and Gray all speak about the body in a way that resembles how playwrights speak about text. They use words like rhythm, beats, articulation, pause, and structure. The language of movement – natural gesture (from the body), amplified gesture (as we see in mask work), and transmitted gesture (as we see in puppetry) – could be thought of as text; it is a code the artist is using to convey their intention to the audience. Bebê de Soares, agent/manager of the Amazonas International Network based in Chile, represents several artistic companies that create non-verbal work. “The body tells us what words cannot,” de Soares states. “With many of my artists I represent, the director, or the artist serving as the ‘outside eye,’ is the driving force, not the text. Text is just another element. Music and dance … visual art … these are a vital. Children need a diverse diet of arts and culture, and they can’t receive that if they only see plays that are spoken. Other disciplines can be theatrical.”

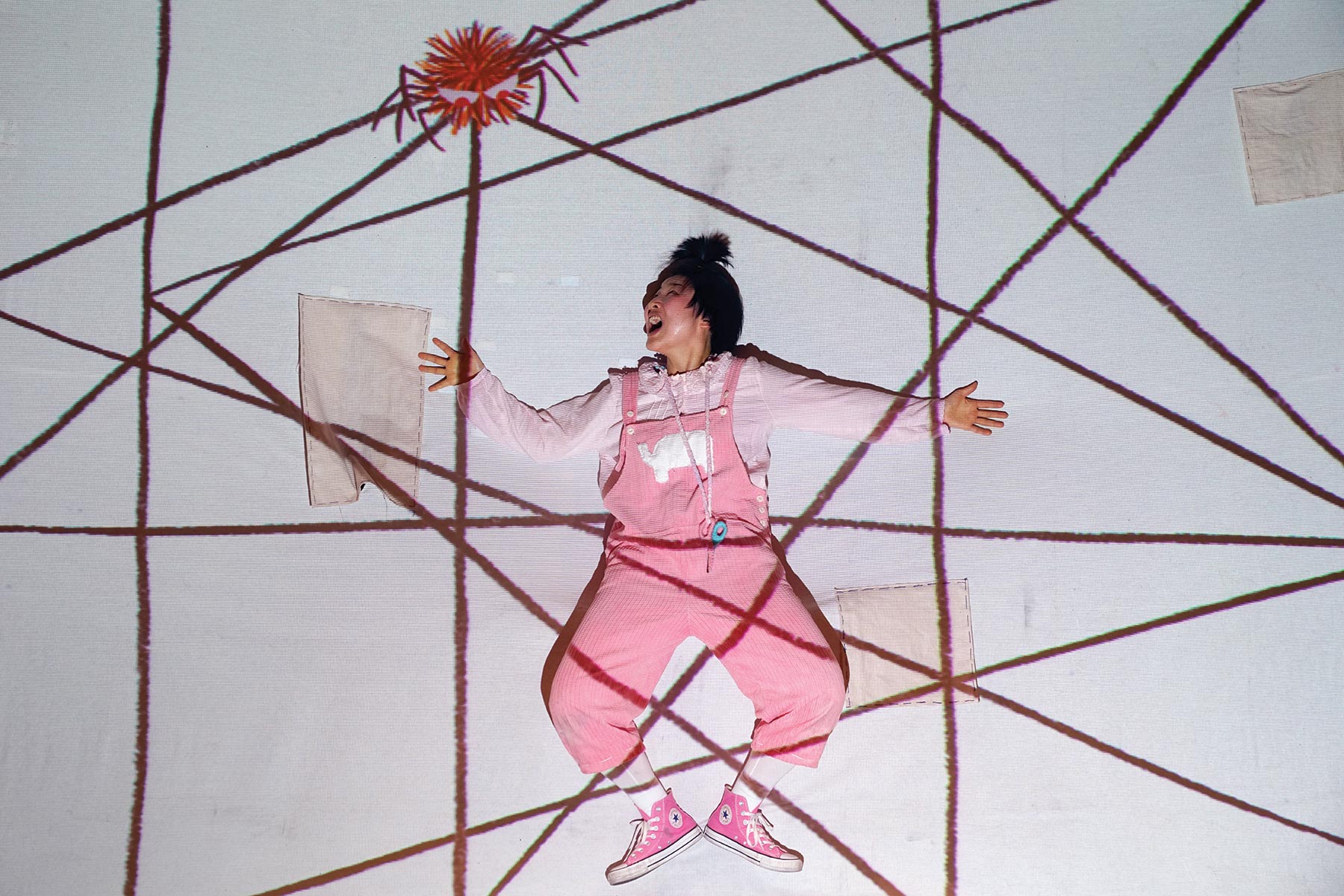

Production image of Yao Yao by Brush Theatre.

Artists as Scientists-at-Play

The development process of non-text-based work is unique to each creative team, but there are a few key characteristics underpinning each one. As artists describe the impulse(s) for their work, there is an immediate sense of a playful scientist laying out the parameters of a new experiment. There is a spark – a flash of curiosity that propels the artists into pursuit of new ways to connect their imagination and joy of creation with their audience. Artistic Director Jun Lee of Brush Theatre in South Korea shared that their productions start from very simple explorations. “The starting point for our production of YAO YAO (a story of a little girl who doesn’t want her dad to go to work) started with a length of yarn,” said Lee. “We started brainstorming and generating ideas with a simple stage set. I think that in creating non-verbal forms of work with everyday materials, many audiences from adults to children can fully understand and sympathize with the character who wants her dad to stay home and play.”

Air Play by the Acrobuffos (Seth Bloom and Christina Gelsone of the United States) is an epic amalgamation of cirque, vaudeville, juggling, physical comedy … and physics. It also started with a relatively small spark of an idea – a what if? “We were fascinated with Daniel Wurtzel’s air sculptures,” says Bloom, “and we wanted to work with him and see what would happen.” This collaborative experiment with air currents and objects needed a very critical component: a very big space. To say that a 30’ x 30’ rehearsal space with a 20’ ceiling is expensive in New York is a gross understatement, but the specificity of their artistic inquiry actually drew unexpected collaborators. “We had a sense of what kind of space we needed to play and experiment. We put feelers out, and we were shocked when Flushing Town Hall responded and said their space wasn’t being used at a certain time and that is was available for us,” Gelsone shared. “It was the opposite response of what we expected. It seemed like an impossible request, but it was a matter of finding a space with the right dimensions and making the timing work.” The space in Flushing Town Hall, a rehearsal space, and grant support provided by Daniel Hahn at Cleveland’s Playhouse Square, and a week at The New Victory Theater, allowed Air Play to find its size and scale.

In any laboratory, sometimes experiments go wrong and yield important but unanticipated discoveries. Manual Cinema, a Chicago-based company that uses overhead projectors and live-feed video cameras to create cinematic visual stories, had a breakthrough moment when the dimensions of the venue they were performing in couldn’t accommodate their existing set-up. This inspired them to flip the screen on-stage (which made the overhead projectors and the performers visible to the audience), and add an additional screen above so the audience could watch the full cinematic composition. “Because the puppeteers were no longer hidden, it demystified the tactile ‘presentness’ of the medium,” said company member Sarah Fornance. “The audience could see us making movies in front of them, as well as the movie itself. It was a major turning point for us, and it allows audiences more agency over how they engage with the performance. They can choose what to watch when, and create an experience that

is uniquely theirs.”

For many companies making non-verbal work, this scientific-experiment-phase continues long after the piece premieres, which is a significant departure from text-based work. “Many artists I know tell me they don’t really begin to understand a piece until they have performed it a hundred times,” says Jim Weiner, of Boat Rocker Entertainment. “Implicit in that statement is that the development process can continue long after the point that the casual observer would consider a work ‘finished.’ Many artists consider every work they make to be a work in progress, even after performing it publicly for a long time.” Particularly in more abstract, poetic pieces, the audience shapes each performance and offers new discoveries to the artists. They never take their finger off the pulse of how each moment is connecting with the people in the room.

Diverse Entry Points for Audiences

Young people are infinitely unique in how they interact with the world around them. Text-based theatre has been working diligently to be more inclusive of more diverse audiences, and American TYA practitioners are more aware of the urgent work before us than we have ever been. Non-verbal theatre holds unique possibilities for widening that embrace and diversifying theatre even further, because it offers different “entry points” for its audience.

Actor, playwright, and deviser Tia Shearer has been part of the development of several new TYA plays through New Visions/New Voices at The Kennedy Center. She’s been collaborating with Arts on the Horizon to create Theatre for the Very Young (TVY) and was surprised to discover that her writing was becoming more and more visual. “I started following this quieter muse, but I was surprised by it. I am such a talker! And a reader! I thought I got into theatre in the first place because of the deliciousness of words! It turns out, I was more interested in what lay beyond the words, or what the words could conjure.”

Like many TYA and TVY practitioners, Shearer constantly grapples with how to define “text” and “story” in relation to non-verbal work, but finds the impulse or essence of the work quite clear. She recalls bringing her first non-verbal show with Arts on the Horizon to a school with a large population of ELL students. “I had read about how Rowan Atkinson purposely brought his Mr. Bean character to a festival in France to make sure the non-verbal humor would translate. I so hoped it would work for us, too. I had no idea it would work so well. The kids were delighted! They laughed at all the places that made sense to laugh. It occurred to me then that perhaps they were extra-excited and engaged because this work let them in. They weren’t spending energy trying to understand what was happening. We were speaking their language.”

Brush Theatre shared an experience they had at the Edinburgh Fringe Festival in 2014 with their namesake performance, Brush – a production that does not use any artificial acoustic or lighting elements, only actors, live music, and the actors’ drawings. “A mother was looking for a show to watch with her daughter. Her daughter has Asperger’s syndrome, and the mother said she tries to choose experiences that will not irritate her daughter. Her daughter enjoyed the performance very much and has become friends with Brush company members and is meeting them again in Edinburgh each year,” says Jun Lee. South African playwright Lereko Mfono shared a similar discovery about how young people connected with one of his non-verbal plays. “South Africa has a very rich text-based history in theatre, and audiences are just more accustomed to words unless it’s dance work,” Mfono states. “But I found young people connecting to the [non-verbal] form in a far more visceral way, much more than I had witnessed in text-heavy theatre.” The TYA community may not yet have language to describe why and how audiences are connecting with non-verbal work, but they intuit and recognize the different varieties of attention their work evokes from the audience.

“What I’ve found in all the work I’ve seen all over the world is that children are rarely overestimated. If you trust their intelligence, they will trust you and follow you, even to places adults will not.”

— Bebê de Soares

Building Worlds of Meaning

If text doesn’t drive the audience’s experience, what does? The touchstone that these works share is the world that is built on stage and how the characters inhabit that world. In other words, rather than the work filling a container that already has a sense of its own size and shape, the work and the container evolve together.

A piece such as Nest by Theater de Spiegel in Belgium is best experienced in an intimate space. The scenic elements are constructed of natural materials – woven baskets, carved wood, linen tunics – and the audience is immersed in this warm, highly tactile environment. The performance begins and ends quite gently with no clear directive of when the play starts – simply a “gathering up” and later a release of the audience’s attention. The world is an extension of the performer’s exploration of a nest of eggs and the birds that are tending them. The gestures are gentle (eggs are fragile), the music is abstract but with brief, soft, recurring melodies. To someone unaccustomed to non-verbal theatre, it can be challenging to allow yourself to “sink into” the experience and just be present in the moment without trying to connect that moment to what came before and what you anticipate coming after. The performance is a series of “phrases” of meaning emanating from the natural customs of birds and eggs, but these phrases do not follow a linear life-cycle. Instead they provide a collection of impressions created by visual and tactile elements, sound, and movement.

In The Polar Bears Go Up, a collaboration between Fish & Game and the Unicorn theatres in the UK, there’s a clear story line. The elements we see on stage are just as unique to the story as the elements composing Nest, and these are thoughtfully and imaginatively crafted. Audiences accustomed to text-based work may find themselves on a more familiar landscape. The dramatic tension is always between the two polar bears and their goal (never between the polar bears themselves), and their journey progresses slowly. We watch them wake up, wash up, make toast, have a glass of milk – there’s no hint of rocket ships or space adventures until at least a third of the way into the performance, but the audience is captivated nonetheless. Non-verbal work often exists (quite successfully) in a world of dramatic time that seems very slow when compared to text-driven work.

Whether the work is abstract or concrete, linear or impressionistic, there is a discernible, gravitational force holding everything together … some universes are just more distant from the text-universe than others. “What I’ve found in all the work I’ve seen all over the world is that children are rarely overestimated,” says de Soares. “If you trust their intelligence, they will trust you and follow you, even to places adults will not.”

But Is It Theatre?

Non-verbal theatre challenges our assumptions about what theatre is and can be. Traditionally, Western theatre privileges plot, which is revealed by the characters through language and action. There is an expectation of an escalating sequence of events that culminates in catharsis or revelation. Without the specificity of language (text), do the remaining elements support the architecture of the plot? In some non-verbal work, those elements absolutely do, but by a strict Aristotelian definition, is it theatre?

Non-verbal work exists along a continuum and embraces varying degrees of ambiguity. It offers its audience an experience that may not be cathartic, but does contain a satisfying emotional density. By the nature of its form, it often un-silos the categories imposed on artists (director, actor, playwright, designer) and shifts the dynamics of artistic collaborations. It has the capacity to transcend language barriers and is rich in sensory and cognitive stimulation. Regardless of these attributes, non-verbal theatre’s underlying intention (like its text-based counterpart) is to connect live performers with a live audience, in present time and space, for a meaningful experience.