Years later, while endeavors to involve children in the development and devising processes of new work have become more prevalent in recent years, there still remains a lack of focus on understanding how youth respond to live performance. Yes, most theatres have talkbacks now where a handful of audience members can ask questions to the cast and crew; yes, some theatres do post-show workshops to extend the production experience (though the majority still emphasize pre-show activities to both prepare and ramp up excitement for the show); and yes, many theatres track audience reception by seeing who comes back for another production. However, none of these activities systematically capture children’s perspectives of experiencing the live performance, how they internalize the experience, and what it means to them on a deeper level than liking/not liking the production. To date, Matthew Reason’s 2010 book, The Young Audience: Exploring and Enhancing Children’s Experiences of Theatre, remains one of the few investigations of analyzing post-show student drawings to unpack young children’s reception to live performance.

One potential explanation for the lack of research on this topic comes from the inherent difficulty in evaluating children’s subjective response to live performances. In addition to the age-old limitation of not having enough time for anything but the performance itself, particularly when working with school audiences, the field lacks robust evaluation tools that are developmentally-appropriate, engaging (I thought this was supposed to be a break from school!) and capture children’s experiences in meaningful ways for both the theatre and the children themselves.

Supported by a 5-year Arts Education Impact grant from the Pierre and Tana Matisse Foundation, The New Victory Theater (The New Vic) took on this challenge in an effort to move beyond traditional audience reception metrics and capture the impact of live performances from the perspective of the very audience members they serve – children themselves. Under the leadership of Courtney J. Boddie and Lindsey Buller Maliekel, the theatre’s directors of education for school engagement and public engagement, respectively, The New Vic collaborated with Alan Brown and Megan Friel from consulting firm WolfBrown on the first of its kind large-scale research endeavor into child audience reception.

Dennier Alamanos in Chotto Desh, choreographed by Akram Khan and directed by Sue Buckmaster. The New Victory Theater, New York, NY. Photo by Richard Haughton.

The Process

Finding Focus

The New Vic engaged in a series of retreats with key staff members and teaching artists to determine collaboratively what they wanted to focus on for their research study, with one major theme bubbling to the top of the list – IMPACT. But not just the impact of the arts on children’s test scores or missed school days, as is often the rationale made to funders for investing in arts education. As Maliekel noted, “Those are interesting but they don’t match why theatre educators think the arts are important for young people. Those were indicators of what happens to young people when they experience live theatre but no one ever says, ‘The real outcome was that it made my social studies test better!’” Boddie echoed this sentiment, describing how “the reasons we identified as most impactful to us and to the young people we work with were not being talked about or in the research.”

The New Victory Theater and WolfBrown set off on a 5-year research endeavor to evaluate the intrinsic impact of live performance through in-theatre surveys, which were based on the larger body of research led by Dr. Dennie Palmer Wolf and Dr. Steven Holochwost of WolfBrown. The study focused on four primary outcomes of interest: 1) Personal Relevance – how youth think about their own lives or those of people they know; 2) Social Bridging – whether and what they learned about people different from themselves; 3) Aesthetic Growth – how youth responded to and interpreted the diversity and novelty of artistic genres and modes of presentation; and 4) Action Motivation – whether watching a live performance motivated youth to learn how to perform like the artists they watched on stage. Importantly, The New Vic did not attribute traditional valences of “good” and “bad” to each of these outcomes but rather remained open to what young people identified as the impact of live performances on themselves, their relationships, and their understanding of the world at large. In this way, the team inherently gave agency to the young people to define their theatrical experiences for themselves.

On a broader level, the team also explored whether and how youth responses differ across different types of live performances in an effort to better inform season curation both at The New Vic and across TYA companies at large. Further, the team sought to use this research endeavor to develop a shared language for the field of TYA to enable necessary conversations around what youth audience reception means, what intrinsic impact means, and what both can ultimately tell theatre artists, producers, and educators about their field and the core audience it serves.

Arts for Everyone or Arts for Anyone?

In the planning process for evaluating the intrinsic impact of live performance on young people, The New Victory Theater realized that “the schools who were working with The New Vic were essentially finding us on their own. They had enough agency to seek it out,” noted Boddie. Thus, while The New Vic had extensive partnerships with 170 New York City schools, this was still only a small fraction of the city’s 1.1 million public school students.

Like The New Victory Theater, prioritizing equitable access to high quality arts and arts education permeates the field of TYA, with theatres across the US engaging in initiatives to connect with young people in traditionally underserved and low-resourced communities. While the tagline of Arts for Everyone can be found in mission statements and program materials across the TYA landscape, with the intent of offering arts to all children and families, more often than not TYA companies often support arts experiences for a predetermined group based on access, means, and knowledge. That is, only people who have physical access to the theatre (e.g., proximity, transportation, etc.), the means to attend such a performance, and the knowledge about opportunities to engage in live performance make up the “Everyone.”

Indeed, at The New Vic, they were still in the realm of “everyone,” missing large populations of students who did not have the access, means, or knowledge to engage in a New Vic performance. As Boddie described, “What about the other schools who don’t have the ability? After budget cuts and NCLB (No Child Left Behind) and pressure on standardized tests, national data shows that arts education opportunities have shrunk in low-achieving or under-resourced schools. Do we have the ability – and the political will – to help find schools or help schools find us in order that many more students experience the arts?” In essence, New Vic was seeking to open up the Arts for Anyone.

Motivated by this sentiment, The New Vic developed the Schools with the Performing Arts Reach Kids (SPARK) program as the foundation for its broader research study. SPARK uniquely targets young people from underperforming and under-resourced New York City public schools and is the first program of its kind to specifically measure and analyze the intrinsic impact of live performance and associated arts education experiences. Across a three-year period, students in New Vic SPARK schools see nine live performances and engage in 45 performing arts workshops that offer students opportunities to increase their creative skills in circus, puppetry, theatre, dance, and other performing art genres. New Vic staff and teaching artists work closely with teachers and the broader school community, and also offer family programming for families to see shows with their children.

Preliminary Findings

Over the past five years, The New Victory Theater and WolfBrown have gathered an immense amount of data, including more than 3,200 post-show student surveys across the 15 shows. While the analysis process continues, early findings illuminate that the impact of live performances is not only more complex than standard academic metrics but that the process of data collection itself may provide additional opportunities to extend the performance experience and enhance the intrinsic impact of such performances.

Shows Have Feelings Too

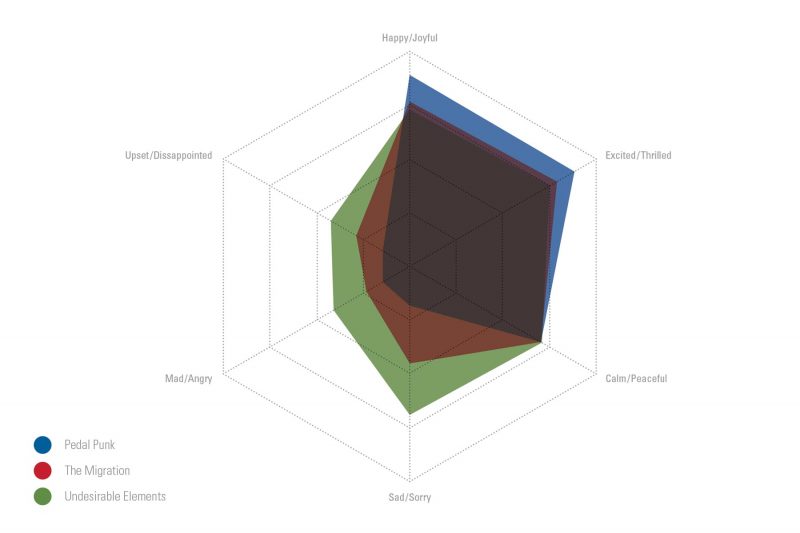

Traditionally, TYA has used “liking” as the main metric for summarizing young audiences’ reception to performances. The more youth like a performance, the better. However, this simple dichotomy of like/dislike fails to capture the rich variety of emotional reactions an individual may experience from viewing a live performance and ultimately undermines the experience of young audience members. As Brown described, “We’re doing a disservice if the only way we’re adjudicating their experience is did they like it or not? We can do better than just like or not like. They are complex.” Indeed, students not only reported varying emotions experienced within the same show but also different emotions depending on the type of performance. Brown continued, “TYA wants to create an experience where the young people are ‘happy’ but we’re most excited to see that in these shows there is more than just positive affect. Young audiences should have art that matches the full range of emotions that they themselves experience in their own lives.” Maliekel echoed these sentiments: “When we talk about what kind of art we are creating for kids, we were excited to see that there were sad and calm/peaceful reactions. It’s interesting to know that they felt sad/sorry and identified it was impactful and identified it was incredibly interesting.”

This graph compares the emotional footprints produced by three different performances – a narrative performance, a dance performance, and an acrobatic performance. The closer to the point each performance’s emotional footprint extends, the more strongly students reported experiencing the corresponding emotion. For example, Pedal Punk, an acrobatic work, sparked high levels of happiness, while Undesirable Elements, a narrative work, stirred feelings of sadness.

The diversity of genres presented by The New Victory Theater – including puppetry, circus, traditional narrative – provided youth with an opportunity to experience a broad range of artistic performances, which proved valuable for uncovering young people’s multifaceted reactions to live performance. Despite this, the majority of TYA companies remain focused on driving positive reactions, placing higher value on youth liking a show; this influences season curation and can perpetuate the repetitious cycle of producing the same genre or type of productions because kids “like” them. While breaking out of this paradigm is not easy (Popular book titles sell!), the results from The New Vic/WolfBrown’s initiative suggest using “liking” as a primary metric falls far short and fails to respect youths’ sophisticated reactions to live performances. As Brown noted, “[The results] show youth can have an authentic reaction to a work of art that is unique and legitimate.”

Curating Diversity

As part of the post-show surveys, students responded to the open-ended question, “What questions would you like to ask the performer?” The diversity of live performance types came through in student responses and exemplified the value of curating a season with different types and genres of artistic experiences. In general, shows that were more acrobatic tended to have more questions about the artists’ training and skills; more narrative shows had more questions about the plot and characters, as well as curiosity regarding the well-being of the character. There were also some anomalies – if there was magic, then there were tons of questions and curiosity around magic regardless of the show type.

Despite the inherent value of offering varied types of live performances, The New Vic acknowledged that teachers often select productions based on time of year, academic connections, and entertainment value, which makes popular book titles or “fun” shows an easy out to get school audiences in the door. However, Boddie and Maliekel note that the onus falls on the TYA company to help make the connections for teachers, particularly for performances that may not have obvious connections, to avoid the monotony of always producing traditional types of shows known to sell. The New Vic helps teachers think about curating performances specific to their own students and their goals for their students. For example, Boddie described how Nivelli’s War, a collaboration between Ireland’s Cahoots NI and The Lyric Theatre, easily provided an academic connection as the show is inspired by a true story from the aftermaths of WWII. At the same time, when speaking with teachers, she highlights the narrative quality of the show as well as the highly engaging artistic component that continues to amaze student audiences – magic. Alternatively, if teachers want a more skill-based performance, The New Vic offers acrobatic and circus performances. While not all productions may fit all three criteria, streamlining seasons just to fit such criteria jeopardizes the season into becoming one of likes and dislikes, rather than one that brings a complexity of genre, story, emotion, and creativity to the lives of young people.

Value of Repetition

Educators already know that repetitive exposure to new concepts can enhance learning, particularly when each subsequent exposure provides a novel way to engage with and experience the concept to be learned. TYA educators often consider this technique within a single production experience – through such tactics as pre-show workshops and residencies, the performance itself, and post-show talkbacks – but through the SPARK program, the New Vic enabled the unique opportunity to not only evaluate the intrinsic impact of a single live performance but the cumulative impact across repetitive exposure to live performance.

While the experience of seeing an individual performance evoked multifaceted emotional responses, engaging with multiple performances over the course of the SPARK program enabled students to more deeply engage with the experiences. As Maliekel noted, “Once they saw multiple performances, they are able to differentiate responses and they become much more complex. They were able to make complex comparisons between the shows, what they personally liked/didn’t like, and why.” This suggests repetitive engagement deepened students’ ability to engage with and reflect on the artistic experience, thus potentially enhancing the overall intrinsic impact. This may be particularly relevant for students with little or no prior exposure to live performance, and while this framework may not be feasible for all TYA companies or school districts, supporting multiple opportunities for students to engage with diverse live performances can provide a more enriching and impactful arts education program.

Meaning Making through Surveys

While not the initial intent of the project, post-performance surveys ended up serving a dual purpose – in addition to being the primary data collection mechanism, the surveys also became a core component of students’ meaning-making process by providing an outlet to reflect on the live performance. As Brown described, “The process of filling out a survey is part of the post-performance meaning-making process where a work of art resonates and bounces around in these kids’ heads and there’s a lot of nervous energy afterwards.” Students completed the surveys directly following each performance, not leaving their seats until they were finished, creating a space for reflection in real time to capture immediate thoughts, feelings, and reactions. Brown noted that more often than not, theatres put the majority of resources into preparing students to come to performances, versus engaging with them afterwards, and suggested that even the simple act of completing a short survey while the performance is still fresh in students’ heads may be a strategy that theatres can implement to help probe students’ thinking and extend the experience of the live performance into children’s real lives, even when the time and resources do not allow for more elaborate post-show activities.

To Use Data or Not to Use Data, That Is the Question!

The emergence of new technologies enables data collection on everyone and everything at all times of the day, and while the field of TYA has and will likely continue to use data-driven strategies to make decisions around season curation, The New Vic/WolfBrown’s initiative provides another type of TYA metric that presents a new perspective directly from youth. For Boddie and Maliekel, having young audiences provide feedback offers valuable information for understanding whether and how The New Vic fulfils its mission to engage young people in high quality arts experiences that are personally relevant, expand perspectives, and ignite interest in the arts. As Boddie explained, “What are we doing from an education standpoint? Where do we put our energy and dollars that will affect how impactful these shows are for young people? And how do we ensure they are as impactful as possible? [The data] provide more ways to make decisions in the education department.” Similarly, Maliekel described how The New Vic education department focuses on artistic programming but not on curating: “Our role is about building anticipation, making those entry points, and creating agency and access in young people’s own critical thinking, creativity, and relationships. Data gives us better language, and ability to describe these critical outcomes we seek.”

However, not all theatres may want such information. Indeed, Brown described data-driven TYA as a national issue, asking, “To what degree do you want to know the impact of your programs and why? Will it affect the way you curate programs or not? This may be different for different organizations – some are hungry for this information; others see it as static and believe their work resonates and that’s all they need to know. It becomes an ethical question – what is the role of audience feedback in an artistically driven organization?” Just as the surveys enable a meaning making experience for students, so too should this question for TYA organizations.